Listen to this story:

AMININ

[V.] To confess

Two years ago, I left the Philippines to take an intensive writing course in Winnipeg. I prepared myself for the expected: grammar lessons, peer editing groups, and countless caffeine-fuelled drafts. What I didn’t expect was to learn how to write in an ancient script — one my ancestors inscribed on delicate palm leaves and sturdy bamboo before Spanish colonialism led to its near-extinction over 400 years ago.

While I have spent most of my life in the Philippines and was aware of Baybayin, my interest in it didn’t spark until after I had been in Winnipeg for about a year. I had considered the script, separate from languages or dialects like Tagalog, to be a relic of the past until one lazy afternoon in August 2024.

It started when an Instagram post caught my attention. The black-and-white image of familiar hand-painted symbols on a piece of paper contrasted with soft red text that read “babayin baby.” The post promoted a workshop in Winnipeg teaching the ancient script.

Seeing a post about a Baybayin workshop wouldn’t have been surprising if I had been in my homeland. Its resurgence in the Philippines, garnering media attention in the 2010s, made it popular as a decorative script for tattoos, clothes, and logos. Seeing this cultural practice make its way to Winnipeg intrigued me.

When I was in the Philippines, intrigued was the last word I’d have used to describe cultural practices and events. Tradition was simply the backdrop of daily life, something I passively participated in, like reluctantly wearing historical attire or performing folk dances during Buwan ng Wika (National Language Month). Eating with bare hands or curing illness with hilot (ritual healing massage) was ordinary. And the sheer number of annual fiestas — an astounding 42,000 — highlights how cultural celebrations are routinely part of life.

Reconnecting with culture was a foreign concept to me because living as a homeland Filipino (someone who resides in the Philippines) meant I didn’t have a chance to feel disconnected from my customs and traditions. My time abroad gave me a newfound appreciation for Filipino cultural practices and shifted my perspective from viewing culture as a lived experience to recognizing it as a privilege — one I used to take for granted. Most diasporic Filipinos (those who have Filipino heritage but live outside the Philippines) do not have that privilege.

After living in Canada for almost two years, I’m grappling with my identity. Am I a homeland or diasporic Filipina? In the most literal sense, I belong to the diaspora as a temporary resident in Canada; however, my sense of self remains firmly rooted in my homeland. It’s hard to identify as one or the other when I’m straddling the space in between.

This experience is amplified for most Filipino-Canadians who deeply feel the tug and pull of their multicultural identities. Many of them spend most, if not all, of their lives away from the Philippines, making it challenging to celebrate and stay connected to their cultural identity. Events like Baybayin workshops are an ideal space to connect with and experience some of the cultural practices I had taken for granted before I left home.

Navigating cultural identity within the diaspora comes with its own struggles, from preserving traditions to finding a sense of belonging in a different cultural landscape. This also includes dealing with microaggressions, like comments that leave one questioning if they are Filipino enough to practice their customs.

Here’s a confession: I’ve committed those microaggressions too. I’ll never forget when I heard a close friend of mine, who grew up outside the Philippines, speak Tagalog for the first time. “Kaliwa,” they said. Their accent made it sound like their tongue curled with each syllable – entirely different from the firm, choppy pronunciation you’d hear from a native speaker. To my ears, it sounded like they said, “cow lee woah,” and I couldn’t stop laughing. In retrospect, what I thought was harmless, playful teasing might have affected them more than they let on. It was the only time I heard them speak Tagalog unprompted.

This memory played through my head as I sat in my first Baybayin workshop. I couldn’t stop thinking about what purist/traditionalist Filipinos would feel about a Filipina learning Baybayin in a foreign land, after ignoring opportunities to do so in her own country. They must be rolling their eyes or having a good laugh – like I did when my friend spoke Tagalog.

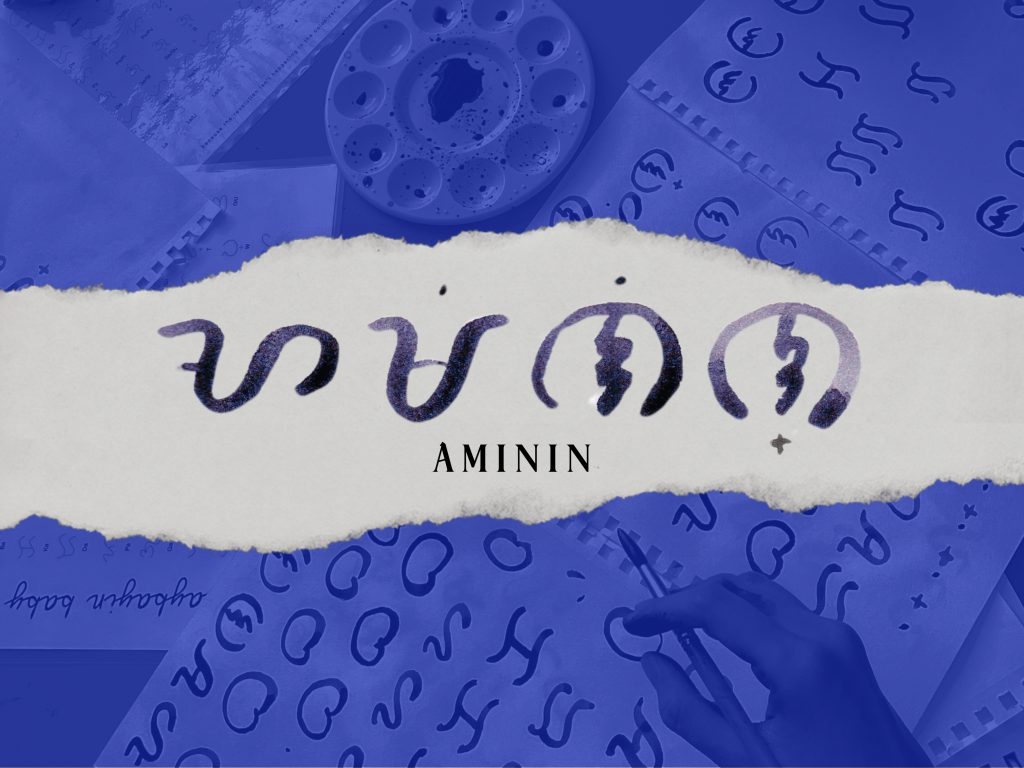

BAYBAYIN

[N.] An indigenous script

I asked my grandmother – Nanay, to me – if she knew of Baybayin.

“Ano yun?” she asked, responding over FaceTime.

Her puzzled expression mirrored my own. She wondered what I was talking about. I wondered why she asked what it was in the first place. Surely, Nanay would know the ancient script of our ancestors.

“Ah, Alibata,” I answered, after realizing she probably recognizes it by a different term.

“Oo,” she said, confirming my hunch.

Baybayin used to be synonymous with the term Alibata since Filipino scholar Paul R. Versoza coined it after the Arabic alphabet. In 2014, the Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines published a post to confirm Baybayin as the proper term.

Before coming to Winnipeg, my exposure to the script was limited to fleeting mentions of Alibata in history lessons. Baybayin was never taught; instead, I learned Abakada – an indigenized version of the Latin alphabet modified to combine consonant letters with vowel sounds heard in native dialects. It was impractical to learn Baybayin. The ancient script became obsolete when conquistadors imposed the use of their Latin alphabet after exploiting Baybayin to aid their conquest.

Way before Spanish colonizers came and named my homeland after their king, Philip II, my ancestors used Baybayin to write short messages. However, they didn’t use the script to formally document their stories. They passed down their knowledge and history through oral storytelling, which makes it difficult to trace exactly where and how the script came to be. European researchers have tried uncovering Baybayin’s beginnings, coming up with different theories. So far, there’s no definitive answer.

Not even Spanish colonizers who documented and observed Indigenous customs could trace Baybayin’s origins, and this was likely the least of their concerns. As they watched how natives inscribed the script on leaves, bamboo, and stone, what mattered to these invaders was that the people they wanted to conquer were already literate. And in the grand scheme of colonization, literacy became a key component in firmly subjugating the archipelago and its people under the banner of Christianity.

With a wide-open opportunity to further Catholicism’s reach, colonizers made it their mission to learn Baybayin to spread doctrine and Christianize natives. Missionaries used the script by including Tagalog and Ilocano translations in religious texts to speed up the process of tightening their grip on the archipelago.

As the Spanish successfully conquered trade routes in Manila, Mindoro, and Palawan, colonization forced the resisting indigenous tribes to move inland, where they lived in isolation in the highlands. These tribes include the Buhid, Hanunoo, and Tagbanwa. They preserved, and are still preserving, variations of Indigenous scripts.

Missionaries eventually dropped Baybayin in favour of the Latin alphabet as Christianity spread. Conquistadors grew frustrated with the ancient script because of a simple reason which still rings true to this day: Baybayin is difficult to read.

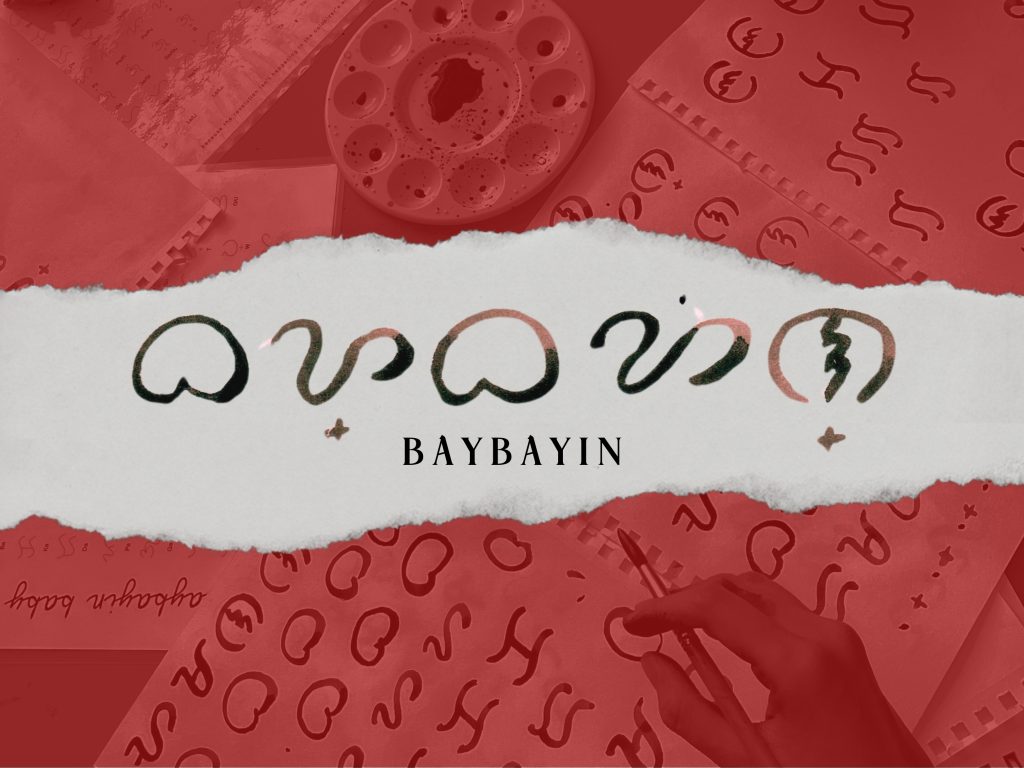

KABABAYAN

[N.] A fellow Filipino

“It’s like an act of remembering,” said Kat Daaca, founder of baybayin baby – a brand offering custom Baybayin products and workshops at markets in Toronto and Winnipeg. “I believe we carry ancestral knowledge — generations of knowledge in us, and it just takes some practice to awaken it.”

She held her first Baybayin workshop at The Forks during last year’s Kultivation Festival, which celebrates the Filipino community in Winnipeg. These workshops welcome anyone curious about the script to learn in an encouraging, low-barrier environment. “It’s so much better to do this work with a community,” she said. “I think that people are longing for spaces where we can connect with one another, connect to the self, and connect to our ancestry.”

Kat serves as vice-president of the Manitoba Filipino Business Council and chairperson of Kultivation F.A.M.D. (Food, Art, Music, Dance). Equally significant is her role as a key player in the resurgence of Baybayin in Winnipeg — a city that’s home to one of Canada’s oldest and largest Filipino communities.

Winnipeg’s Filipino community was established in the late ‘50s when the first Filipino families arrived, including those who moved from the U.S. and other Canadian provinces. Opportunities in the medical field made the city an ideal home for families like Dr. Paulino and Clara Orallo, who arrived in 1962 and had the first Winnipeg-born Filipino a few years later. In the late ’60s, the Filipino population grew to 500 after a wave of Filipina immigrants were recruited to work in garment factories, leading to a thriving community in the Maples area. Today, Tagalog is the 2nd most-commonly spoken mother tongue in Winnipeg.

Kat recalled an experience at one of her workshops where a participant told her she should learn Tagalog if she plans to continue teaching Baybayin. “I agree, I do need to learn Tagalog, but I don’t necessarily think that’s a prerequisite,” Kat said.

“Living outside the Philippines, I feel the need to defend my Filipino-ness a little bit more.”

As the only Canadian-born Filipino in her family, Kat learned to speak English as her primary language. About a week before her first workshop, Kat posted an Instagram reel responding to someone telling her she shouldn’t be teaching Baybayin simply because she doesn’t speak Tagalog. Taking this as a “message of not-enough-ness,” Kat spoke about her experience of not feeling Canadian or Filipino enough to engage in cultural practices.

“I’m kind of tired of not feeling enough to do the things that interest me, to connect back to my ancestry, to participate in forms of expression that resists colonial practices,” she said in the reel. “…I am now, as a grown up, validating my Filipina-Canadian experience by fully participating in the teaching and sharing of the pre-colonial script of Baybayin.”

In 2023, online dispute about Filipino-Americans wearing graduation stoles designed after the Philippine flag took me down a rabbit hole of clashing opinions on Instagram and Reddit. The experience made it clear to me that, at least online, there is a divide between homeland Filipinos and diasporic Filipinos — especially when it comes to cultural expression.

A girl became the centre of the controversy after wearing one of these stoles incorrectly. She wore the stole with the red portion hanging on the right side, which resembles how the Philippine flag is raised upside down to indicate war if hung horizontally.

This sparked some level of outrage among mainlanders. Diasporic Filipinos came to her defense, responding to a video on TikTok where a creator chastised the girl before digging into the legalities of wearing the Philippine flag as clothing — to which I roll my eyes.

This girl did not take a Philippine flag, cut it up, and haphazardly hang it around her neck. No. She wore a graduation stole inspired by the flag’s design, similar to how Manny Pacquiao wore a tracksuit or how Miss Universe Philippines 2020 Rabiya Mateo wore a Victoria’s Secret Angel-esque costume with the colours and details of the flag. And while she wore it incorrectly, she didn’t deserve to be chastised for it.

This was the first time I looked cultural gatekeeping in the face. It made me reassess my perspectives and think about what I’ve done to contribute to the problem.

“It’s easier to write in Baybayin than it is to read Baybayin,” Kat said, addressing about 20 people in her Baybayin workshop at The Forks last December. I was one of them. The workshop was part of the Pasko Pop Up market featuring vendors in the local Filipino community. It marked my first experience learning to write in the ancient script.

Kat explained how Baybayin is a syllabic script, with each character representing a consonant sound paired with a vowel sound. The vowel sound can be determined by a kudlit (a mark resembling a dot, comma, or apostrophe added to the character).

Characters without a kudlit pair their consonant sound with a hard “ah” vowel sound. A kudlit placed below the character creates a hard “eh” or “ih” vowel sound, with no way of indicating which. Similarly, a kudlit above can mean either a hard “oh” or “ooh” vowel sound.

Spanish colonizers altered the script by including a kudlit that resembles a small cross to represent a “vowel killer,” which modifies the characters into hanging consonants.

I could see why, according to historical accounts, Spanish conquistadors described Baybayin as “so defective and so confusing.” It takes a good amount of guesswork to read the script. Unless you grew up speaking or hearing dialects like Tagalog or Ilocano, I can imagine how frustrating and time-consuming it is to read and sound out the words.

Taking a break from writing my name in Baybayin, I noticed a mother and daughter pair bonding over the practice. The daughter, a tattoo artist who goes by Crista Liana, shared how she gets numerous requests from clients wanting Baybayin tattoos. One participant wore a green Barong Tagalog, a sheer men’s formal shirt traditionally made from fibres of piña (pineapple), abacá (hemp), and other natural light-weight materials.

I felt a physical manifestation of belongingness as I learned Baybayin with a community of people exuding warmth and excitement over a shared cultural experience. My heart swelled with admiration for Kat’s work. Had she listened to the person who told her she shouldn’t teach Baybayin because she doesn’t know Tagalog, I would have missed out on a heart-warming experience — an opportunity to celebrate our Filipino heritage together and make connections within the diasporic community.

The workshop reaffirmed my belief that culture, setting aside those practiced sacredly amongst Philippine Indigenous groups existing with their own prerequisites, should be freely shared amongst Filipinos — diasporic or otherwise. There shouldn’t be a discussion of whether a kababayan is Filipino enough to participate in cultural expression.

I felt entirely confident to stand my ground and reiterate this belief. That is, until a single sentence put it to the test.

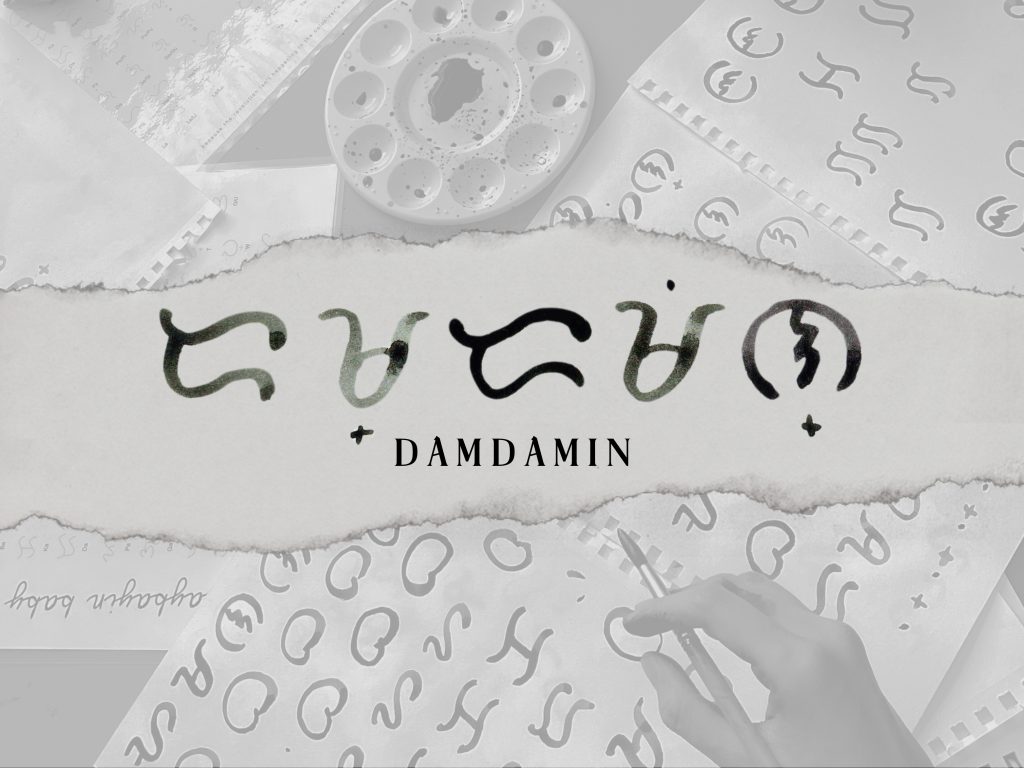

DAMDAMIN

[V.] To hurt emotionally

“That’s why I’m so full of ancestral rage,” Kat said in response to a casual conversation about colonialism’s lasting impacts on Filipinos during another baybayin baby workshop at a Filipino restaurant called Mar’s Sisig. It was the second one I attended, this time as an observer who occasionally shared a few things I picked up from reading about the history of the script.

Perhaps Kat had mentioned the words ancestral rage at some point during the first workshop I attended, or I may have read it in one of her posts on Instagram. Certainly, it wasn’t the first time I heard her say it, but it was the first time I truly listened.

At that moment, I felt a sudden jolt of energy within me. An unpleasant one. I felt the visceral reaction under my skin, radiating from my chest. To distract myself, I started looking through the photos I had just taken on my camera. I could feel my lips subtly curling into a hesitant smile as my body tried to hide my discomfort.

I didn’t understand why I had such a visceral reaction. I couldn’t name it. In retrospect, I felt deep shame admitting how I truly felt: Hearing a diasporic Filipina, born, raised, and residing in Canada, say she has so much “ancestral rage” didn’t sit right with me in that moment. The experience brought up a distorted thought: I never heard my relatives back home complaining about it, so why should she?

Was I no better than the person who made Kat feel like she wasn’t Filipino enough to teach Baybayin? Did I feel like she wasn’t Filipino enough to express her ancestral rage? I winced at the thought.

As I mulled over her statement in the days following the workshop, I realized some part of me unreasonably felt it wasn’t fair that she has time and resources to process her ancestral rage.

Meanwhile, my father comes from a family living in a rural island without access to electricity or running water until sometime in the 2010s. I grew up seeing and experiencing first-hand what life is like for impoverished Filipinos. My relatives had no time to feel, process, or express their ancestral rage. Bigger problems distracted them from recognizing how colonialism impacts them to this day. Instead of feeling ancestral rage, they felt hunger pangs when they couldn’t put food on the table. They felt guilt when their kids cried about how they couldn’t afford new school supplies like their classmates. They felt hopelessness when they couldn’t find ways to cure illness and injury without reliable access to medical care.

I shoved my conflicting feelings and distorted thoughts as far down as I could and didn’t verbalize it for weeks after the workshop. After all, I believe Kat, like every Filipino, diasporic or otherwise, has every right to feel and express her ancestral rage. She is as Filipino as I am. The blood in our veins share the ancestors who came before us, residing in the same land invaded by Spanish conquistadors who enslaved our people, ravaged our resources, and nearly wiped out an entire script.

This experience made me confront a part of myself that was triggered by some level of guilt. Unlike my relatives, I had a better quality of life growing up in a well-developed city. But unlike Kat, I didn’t take advantage of my resources to contribute to the celebration and preservation of my culture.

Beyond the supportive space of Kat’s baybayin baby workshops, my journey toward writing fluently in Baybayin was a gruelling one. One afternoon of writing words became an exercise in relentless repetition: twenty to thirty tries per character, across fifty back-to-back pages, before the words began to flow. Adding to my frustration was remembering how Kat mentioned most workshop participants find writing in Baybayin intuitive. This wasn’t the case for me, and I’d feel frustrated while muttering “Why is this so hard?” under my breath. During the process, I felt almost vulnerable. As if there was pressure hanging over my head to immediately get it.

That afternoon offered a stark insight into the experience of most diasporic Filipinos, who often face the unspoken expectation to instantly connect with and correctly perform cultural practices despite the realities of distance and assimilation.

I’ve had conversations with Filipino-Canadians who shared their hesitation in being involved with cultural practices because they feel disconnected from the Philippines. Local Filipino community leaders like Kat chip away at this barrier, proving it’s never too late to learn, appreciate, and reconnect with cultural heritage. For her, this manifests in channeling ancestral rage into the preservation of an ancient practice. If learning Baybayin from Kat forced me to confront my biases, guilt, and the complex layers of cultural identity in the diaspora, who am I to resent her for it, or take this experience away from someone else?

With a significant global presence reflected vibrantly here in Winnipeg, Filipino culture is a living mosaic – rich and layered. Our connections to culture, and the ways we express them, are deeply personal, uniquely individual, and equally valuable.